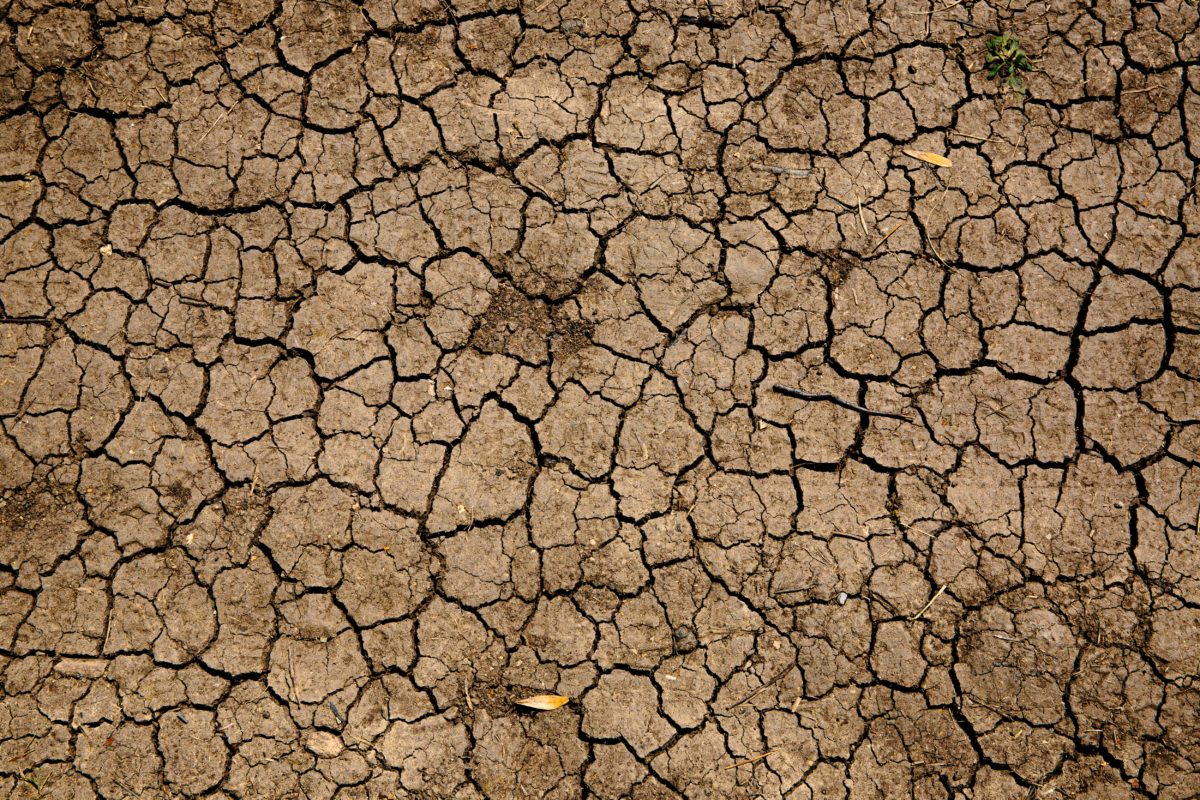

In Africa, the significances of climate change include, among other aspects, the transformation of weather patterns, biodiversity destruction and wider occurrence of more infectious diseases. All these events, in their turn lead to food insecurity, human forced displacement, and water shortages. Marginalised and vulnerable people often experience the worst effects of climate change. They often live in greater poverty resulting in less financial capacity to contend with the challenges posed by changing environments. Partially also for this motive, underdeveloped and developing countries face the most dramatic effects of climate change.

Against this backdrop, it is interesting to consider the extent of the impact of climate change on the African population in Gabon from a human rights perspective, aiming to determine the extent to which the existing legal framework provides protection for people suffering human rights abuses because of climate change.

Attributes that are central to understanding human rights are the following: all human rights are universal, indivisible, interdependent and interrelated. Human rights are universal in the sense that all people in the world are entitled to them. The universality of human rights is clearly shown by Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR): “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” Human rights are also indivisible because they are inherent to the dignity of every individual. Accordingly, all human rights have equal status, and cannot be positioned in a hierarchically because the denial of one right prevents the enjoyment of other rights. Finally, human rights are interdependent and interrelated because any of them contributes to the realization of an individual’s human dignity through the satisfaction of the person’s physical and psychological needs. The implementation of one right often depends upon the realisation of others.

As such, human rights cannot be considered in isolation: their relationship to other rights must also be considered. This is also relevant in the context of human rights in Africa affected by climate change. In the continuing legal debate about accountability and the allocation of responsibility for climate change, a human rights approach should at least to some extent provide a certain structure to this debate. In order to impose a duty on states to protect people against the effects of climate change, it is necessary to determine whether the sorrow caused by the impacts of climate change violate human rights as recognised under existing international and regional human rights legislation.

In this framework, when I focus my research on Gabon, I focus on a country that, in the last decade, has massively reduced deforestation having become the first African country to be paid to curb deforestation. Based on expert assessments, the country was awarded $17 million from Norway through the Central Africa Forest Initiative (CAFI) because of lower emissions from forest loss in 2016 and 2017 than the 2006-2015 baseline. The payment is part of a 2019 agreement between Gabon and CAFI to provide funding worth $150 million for reducing emissions from deforestation and land degradation over ten years. According to the CAFI 2021 Consolidated Annual Report Gabon has preserved the majority of its rainforest since the early 2000s with the creation of 13 national parks and has made significant advances in sustainable management of its timber resources outside the parks. Accordingly, although it only hosts 12% of the Congo Basin forests, Gabon houses almost 60% of the surviving forest elephants in Africa, a key indicator of sound natural resource governance.

In its 2022 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), Gabon commits unconditionally to remain carbon neutral up to and beyond 2050. Provisionally, Gabon, whose territory is 88% forested, will do its utmost to maintain its net carbon absorption at a minimum of 100 MtCO2eq/year beyond 2050.The NDC is a climate action plan to cut emissions and adapt to climate impacts. Each party to the Paris Agreement (adopted 12 December 2015) is required to establish an NDC and update it every five years. Gabon is a party to the Paris Agreement since 2 November 2016.

In June 2017, the Government of Gabon and the CAFI signed a Letter of Intent for $18 million based on the Gabon Investment Plan (Article IV “The Contribution”). This letter allowed the country to meet its 50% emission reduction target (Article I (a) “Purpose of the Letter of Intent”), better plan and monitor the use of land and protect over 23 million hectares of tropical rainforest, nearly 90% of its national territory. This letter provides for several other articles that helped Gabon meeting the objectives, contained in Article II (“General objectives”) of the letter. For example, in Article V (“Efforts to mobilize external funding”) “CAFI will endeavour to assist Gabon to attract private investments to help develop an inclusive, green deforestation-free economy”. Additionally, through Article 10 (“Partnership monitoring”) “[t]he Government of Gabon agrees to ensure, in an integrated manner, with relevant programmes and partners: […] b) joint monitoring and periodic reporting on relevant international development assistance to ensure alignment with the objectives of this Letter of Intent; c) monitoring of the milestones specified in this Letter of Intent [in its Article III], for which updated information will be regularly provided on the website www.pnatgabon.ga to be available to the public”.

To show the willingness of Gabon to act seriously against climate change, Libreville also hosted the 2022 African Climate Week (ACW, 29 August-2 September). The 2022 ACW offered the opportunity to advance climate action considering regional priorities. The week provided a platform for stakeholders and governments to work together and embed sustainability into recovery.

In Gabon, the nexus between human rights and climate change is particularly interesting to assess for several reasons. The National Climate Plan (Plan National Climat), adopted in 2012, is designed to enable Gabon to control its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, reduce climate risks across the country, and enable the reconciliation of environmental protection and sustainable economic development, in line with the Gabon Emergent Strategy (Plan Strategique Gabon Emergent). The green transition is a priority for the country as it has been highlighted in the Programme Indicatif Multiannuel 2021-2027. Against this backdrop, Gabon is the only African country to have appointed, to date, a Minister in charge for the respect of climate, as article 7 of the Ordonnance N° 019/2021 (13/09/2021) relative aux changements climatiques clearly stipulates.

As abovementioned, on 2 November 2016, Gabon ratified the Paris Agreement, which recognizes the need for parties to promote and respect human rights when taking climate action. Also, in the last years Gabon has co-sponsored two fundamental Human Rights Council’s (HRC) resolutions on human rights and climate change: resolution 26/27 (15 July 2014) and resolution 29/11 (22 July 2015). In both resolutions, the HRC emphasized that the adverse effects of climate change have a range of implications, both direct and indirect, for the effective enjoyment of human rights. These include, inter alia, the right to life, the right to adequate food, the right to the highest attainable standard of health, the right to adequate housing, the right to self-determination, the right to development and the right to safe drinking water and sanitation. Additionally, Gabon mentioned human rights in a written submission to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in relation to the need for capacity building to support countries in implementing human rights-based actions (2016). In June 2022, Gabon welcomed the opportunity to submit a Technical Annex to its Biennial Update Report (BUR) in the framework of Results-Based Payments (RBPs) for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, conservation of forest carbon stocks, and sustainable management of forests under the UNFCCC. This document, however, was not referring to the nexus climate change/promotion and protection of human rights. Finally, Gabon also voted in favour of other two HRC resolutions. In resolution 47/24 on human rights and climate change, adopted on 14 July 2021, the HRC emphasized the urgent importance of continuing to address, as they relate to States’ human rights obligations, the adverse consequences of climate change for all, particularly in developing countries and for the people whose situation is most vulnerable to climate change. In resolution 50/9, adopted on 7 July 2022, the HRC recognized that the adverse impacts of climate change negatively affected the realization of the right to food.

Among its other achievements, Gabon joined the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) in 2020, underlining its commitment to combat air pollution and climate change. The CCAC is a voluntary partnership of governments, intergovernmental organizations, businesses, scientific institutions and civil society organizations committed to improving air quality and protecting the climate through actions to reduce short-lived climate pollutants. The UN representatives in the country closely work with local communities and civil society to promote a number of popular initiatives that help regenerate the environment and place the necessities of the local community at the core.

Additionally, Gabon has also ratified the Kigali Amendment (15 October 2016: Gabon accepted it on 28 February 2018) to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (16 September 1987: Gabon ratified it on 9 February 1994). The Kigali Amendment is an international agreement to gradually reduce the consumption and production of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). It is a legally binding agreement designed to create rights and obligations in international law. In converse, the Montreal Protocol is an international treaty designed to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of numerous substances that are responsible for ozone depletion.

In sum, although the government has committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50% by 2025, Gabon is still a country with increasing temperatures, rising seas, and changing precipitation patterns. This presents significant pressure for vulnerable groups, urban infrastructure, food security and the economy in general. Gabonese authorities are undertaking a significant work in contributing to the enhancement in the protection of human rights not only in Africa but also worldwide.

Dr Cristiano d’Orsi is a Lecturer and Senior Research Fellow at the South African Research Chair in International Law (SARCIL), Faculty of Law, University of Johannesburg. He holds a Laurea (BA (Hon) equivalent, International Relations, Università degli Studi di Perugia, Perugia); a Master’s Degree (Diplomatic Studies, Italian Society for International Organization (SIOI), Rome); a two-year Diplôme d’Etudes Approfondies (Master of Advanced Studies equivalent, International Relations (International Law), Graduate Institute for International and Development Studies, Geneva); and a Ph.D. in International Relations (International Law) from the same institution. Additionally, Cristiano has done post-doctoral studies at the University of Michigan Law School (Grotius Scholar) and at the Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria. His research interests mainly focus on the legal protection of displaced and forced displaced persons in Africa, on African Human Rights Law, and, more broadly, on the development of Public International Law in Africa.