OPINION Dr Bright Nkrumah 11 March 2022

The State of Affairs

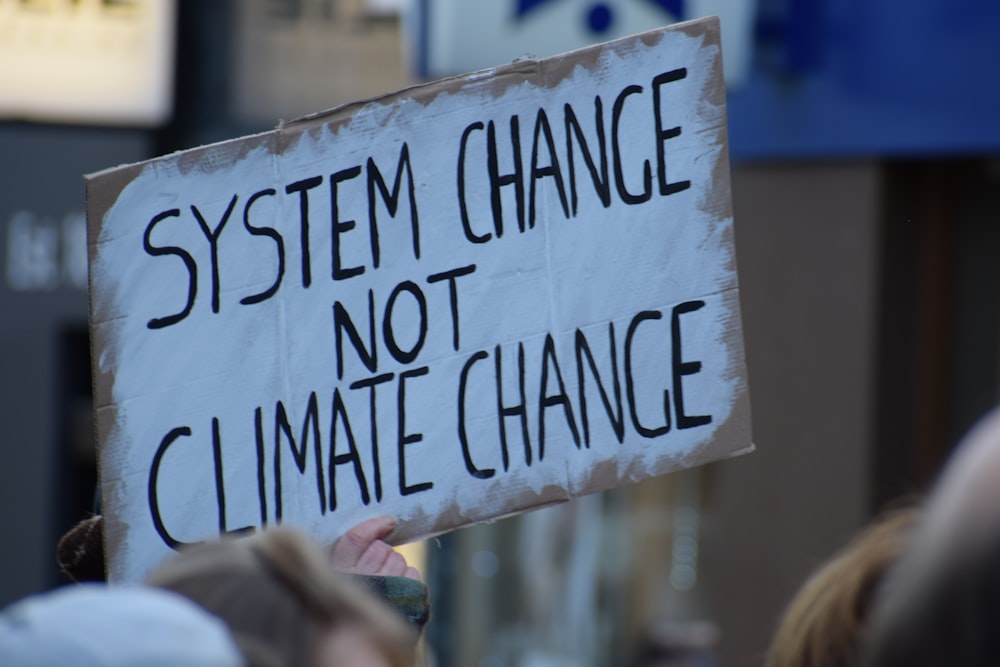

At the turn of the millennium, a growing number of young Africans have joined global movements to agitate for climate justice. [i] The notion of climate justice could be simply construed as the moral or legal obligation of states to use natural resources fairly and equitably.[ii] The call for climate justice is more pressing in this era than in any other given period of time since the projections of global heatwaves, droughts, and floods show a significant intensification by 2050 if radical action is not taken to cap rising greenhouse emissions. [iii] If one pauses for a moment, and reflects, what could be the consequence of this weather pattern?

The Earth and African Wisdom

Perhaps before addressing this discourse, three key concepts ought to be quickly disposed of. The first is, what/who is ‘youth’. This notion is like the hydra, a multi-headed monster. An attempt to define it only creates more confusion. Simply put, there is no universal conceptualisation of youth. As an illustration, whereas the United Nations (UN) define this camp as those between 15 and 24, the African Union Youth Charter expands the bracket to include those between 15 and 35.[iv] At the second layer, the term climate change implies a long-term change in the weather pattern.[v] As this opinion piece is being written, there are muted talks of heatwaves sweeping across Cape Town, and drought cutting water supply to the farmer and pastoral populations in northern Kenya, southern Ethiopia, and Somalia. Having said that, another important term that ties the above two concepts (youth and climate change) together is intergenerational equity. At a basic level, this term may be broadly conceptualised as the fair use of natural resources by the older generation to ensure the younger generation could also use similar resources in the future.[vi] This concept is well articulated by an African proverb, that the land we inhabit was not a gift from our ancestors, but an asset borrowed from our children. As the older generation, we, therefore, have the moral obligation to sustain the environment. But has this been the case?

Inventing Degeneration: Coal and Atmospheric Pollution

Since the birth of the industrial revolution in the 1760s, the exploration of coal has intensified, despite its harmful effect on the atmosphere. Presently, 88 countries are dependent on this mineral as a source of energy. South Africa is one such country. The country’s electricity company, Eskom, relies on 13 coal-power plants that produce about 90% of the country’s electricity. Still, due to the ongoing load-shedding in the Southern African country, the minister for energy has committed to erect more coal plants meeting growing demands.

An increase in coal plants implies that the adverse effect of climate change could be experienced earlier than the projected time frame of 2050. This implies that young people will bear the brunt of these changes, sooner and longer than the adult population. Ramifications will include food price hikes due to shortages, water scarcity, vector-borne diseases, and floods that could worsen accommodation in inner cities.[vii] It is against this backdrop that a growing number of Africa’s youth occasionally mobilise to nudge local and international actors to pursue sustainable environmental practices, or cap rising emissions. Most strikingly, in the last quarter of 2021, a group of South Africa’s youth applied to the Gauteng High Court to forestall the erection of more coal plants. The petition was filed on grounds that the plants will exacerbate the impact of climate change, thereby threatening the survival of future generations.

Youth and Climate Claims: 2021 Snapshot

Whereas climate litigation seems to be an ideal platform for capping emissions, there is also some level of doubt in terms of its potency. The pessimism here was inspired by a landmark case, Juliana v US. Originally filed against the Obama administration in 2015, the case sought to compel the American government to radically shift its energy production from coal to renewables.[viii] After more than half a decade of deliberation, a 9th Circuit Appeal of Court in 2021 dismissed the petition on grounds that it lacks the competence to adjudicate on issues bearing on the allocation of state resources. In other words, it is not sufficient to simply invoke depletion of the atmosphere as grounds for litigation. In the same year, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child briskly discarded an application filed by a group of youth against five G20 countries (Argentina, Brazil, France, Germany, and Turkey) claiming their energy production impinges on their right to life and health.

The Parting Shot

To avert the recurrence of this setback, it is imperative that potential litigants, including those pressing their case before the Gauteng High Court, adopt a creative application of existing legal frameworks. To be exact, a ground-breaking yet underutilised instrument in the climate litigation regime is the Consumer Protection Act. As in South Africa and many other states, this provision imposes an obligation on producers and distributors of goods and services to inform their consumers of the side effects of their commodities. As a consequence, tobacco producers warn their customers of the negative repercussions of nicotine, as well as producers of alcoholic beverages. Sadly, the same could not be said of electricity producers, although the use of coal impacts the health and life of its consumers. Thus, potential litigants ought to consider submitting a climate claim based on withholding key information from consumers, as disclosure could have influenced some to cut back on their consumption to sustain the earth.

[i] Nkrumah, B. ‘Beyond Tokenism: The ‘Born Frees’ and Climate Change in South Africa.’ (2021) 3 International Journal of Ecology 1–10.

[ii] Terry, G. ‘No climate justice without gender justice: an overview of the issues’. (2009) 17(1) Gender & Development, 5-18.

[iii] O’Brien, K., Selboe, E., & Hayward, B. M. ‘Exploring youth activism on climate change.’ (2018) Ecology and Society, 23(3).

[iv] Nkrumah, B. ‘Eco-Activism: Youth and Climate Justice in South Africa.’ (2021) 33(4) Environmental Claims Journal 328-350.

[v] Thuiller, Wilfried. “Climate change and the ecologist.” Nature 448, no. 7153 (2007): 550-552.

[vi] Becker, R. A. ‘Intergenerational equity: the capital-environment trade-off.’ (1982). Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 9(2), 165-185.

[vii] Nkrumah, B. Seeking the right to food: Food activism in South Africa (2021) Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

[viii] Nkrumah, B. ‘Courting emissions: climate adjudication and South Africa’s youth’ (2021) 11(45) Energy, Sustainability and Society 1-12.