COMMENT René Brosius 09 April 2021

Somalia and Kenya do not have a tension-free relationship. Many reasons for this lie in the conflict-ridden history. The border between the two countries is a disputed colonial legacy. Large ethnic Somali minorities still live on Kenya’s territory, especially in the so-called North Eastern Province. The majority of the approximately 1.4 million people living there are ethnic Somalis.

After the collapse of Siad Barre’s regime in 1991, there was also a massive flow of refugees to Kenya, resulting in the world’s largest refugee camp, Dadaab, with around 400,000 people. However, the two countries are also closely and diversely intertwined beyond this. In Nairobi, large parts of economic life are in the hands of Somali businessmen. The Eastleigh district is also called “Little Somalia.” Nairobi is home to much of the NGO scene operating in Somalia, and many prominent and/or wealthy Somali families have at least a second residence in Kenya. Kenya, in turn, provides troop contingents to the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM). Tensions between the two countries are regularly apparent. Travel restrictions, closed borders, and disputes over air travel, export/import sanctions or threats to close Somali refugee camps are frequent occurrences. One of the standing disputes revolves around maritime border demarcation and was brought before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague already in 2014.

What is at stake?

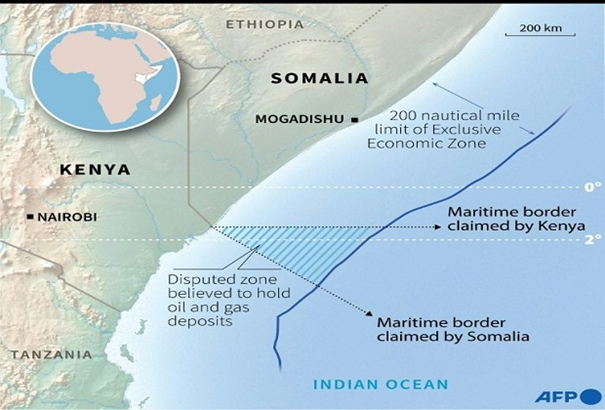

The common land border flows into the Indian Ocean. Here, too, the boundary line is in dispute. However, this has less to do with colonial heritage and more to do with fishing rights and suspected oil and gas deposits. While Somalia assumes that the maritime boundary automatically continues the direction of the land boundary, ultimately up to a distance of 200 nautical miles from the mainland coast, Kenya believes that the maritime boundary should make a 45-degree turn in a northerly direction and run parallel to the latitude in the future. Kenya would thus gain a maritime area of about 162,580 square kilometres (area figures vary widely here). A huge area, especially with regard to the natural resources mentioned above.

On April 7, 2009, the Kenyan Foreign Minister and the Somali Minister of Planning and International Cooperation signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), which had the goal of clarifying the long border dispute. Interestingly, the agreement was prepared by the Norwegian Embassy, which was supposed to provide legal support to the transitional government in Somalia, which had only been in office for a short period at that time. The MOU stated that the final course of the border between the two coastal countries had not yet been conclusively determined and that both parties to the dispute should present their ideas to a commission within a reasonable time. Paragraph 6 of the short document states:

“The delimination of maritime boundaries in the areas under dispute…shall be agreed between the two coastal States on the basis of international law after a Commission [on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, hereinafter CLCS]…made its recommendations to two coastal States concerning the establishment of the outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles. This memorandum of Understanding shall enter into force upon its signature.”

Immediately after the MOU was signed, Somalia declared the treaty non-binding. According to Somali “custom”, the Somali representative was not authorized to sign this treaty. Consequently, the agreement had no binding effect. Kenya, on the other hand, insisted on compliance with the treaty and argued that the treaty had already entered into force upon signing in accordance with paragraph 6. At the very least, Somalia had to adhere to the agreed procedure of paragraph 6 of the Memorandum of Understanding. This would give priority to bilateral agreement over a judicial solution. The dispute remains relevant to both sides up to today. On the one hand, it is a matter of political honour in view of the conflict-ridden neighbourhood. On the other hand, however, it is also a tangible economic issue. For example, the question of whether fishermen can operate in these areas or whether fishing rights can be sold to third parties (e.g. China, Europe, USA, Japan) depends on a settlement of the dispute. Finally, exploration rights for the presumed oil and gas resources are also increasingly at stake.

After years of dispute, Somalia appealed to the ICJ in 2014. Both parties to the dispute had acceded to the agreement in 1989 but reckoned that they had different chances of success in “naked” application. Kenya therefore disputed the jurisdiction of the ICJ and hoped for greater chances of achieving at least a partial territorial success in the context of a bilateral clarification. However, as early as February 2, 2017, the ICJ declared itself competent. The fundamental decision was therefore made four years ago. The decisive factor was the interpretation and legal classification of the MOU. According to this, it was neither the purpose of the MOU to determine alternative dispute settlement mechanisms, nor did the wording suggest this. More far-reaching, however, was the legal classification of such MOUs. The International Court of Justice did not attribute binding effect to them “as a matter of international law.” It is certainly true that such agreements have a certain legal content. However, this could be used primarily in the interpretation of disputes. The issue became topical not only because of the current political crisis in Somalia, but also because the ICJ scheduled the first public hearing on March 15, 2021, after several postponements. Kenya cancelled its participation in the hearing at the last moment. Many Somali commentators interpreted this as Kenya’s withdrawal.

Where do things go from here?

The ICJ may now rule on the matter. It is believed to be more inclined to the Somali side. However, such proceedings can drag on for several years. Until then, the area remains disputed and opens the door to uncontrolled exploitation of resources, as well as numerous environmental pollutions through illegal dumping of waste in the “no man’s land”. Incidentally, the decisions of the ICJ are not enforceable. In the past, countries have simply ignored the court’s decisions. Somalia has therefore not yet won.

René Brosius is a doctoral candidate at the Chair of African Legal Studies at the University of Bayreuth. He is primarily dealing with issues of law and economics in Somalia.