Introduction

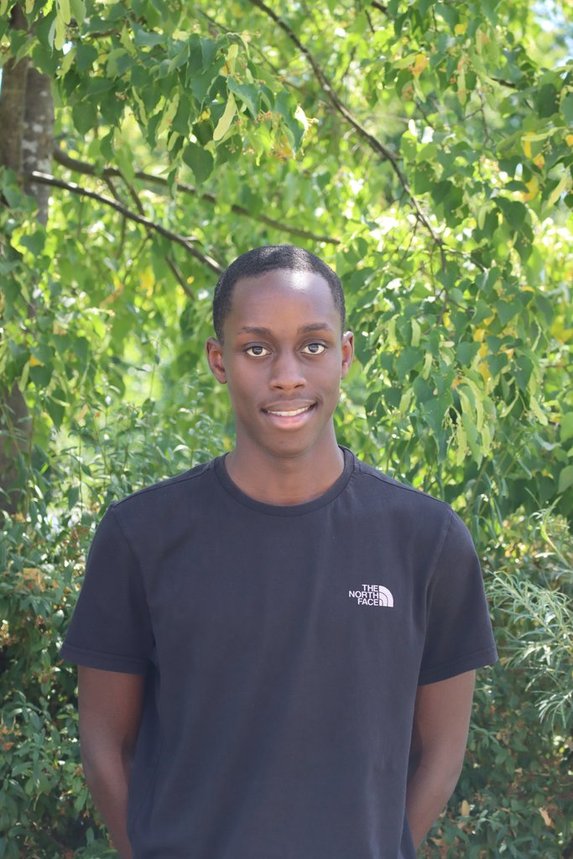

What happens when the laws meant to help people do not quite work in practice? Dr. Cyprian Kambili from Malawi explores this in a conversation with Merlin Mitschker and Aristid Banyurwahe. Recorded during the Law and Belonging as a Relational Practice conference, celebrating the 5th anniversary of the Chair of African Legal Studies, Dr. Kambili shares his experiences studying how law interacts with everyday life across Africa. From small-scale farmers struggling to make a living to the unexpected ways people react to laws and politics, Dr Kambili encourages us to critically deal with our assumptions and pay attention to what inclusion should really look like. His observations are both striking and relatable, reminding us that law is not just about rules on paper but about people, their everyday lives, and the real challenges they face.

The first question might be interesting for readers in general. How would you describe what you’re doing to someone who is not familiar with the academic legal world? What do you do?

My research interests are mainly in law and economics – particularly in how law can promote inclusion, or, sometimes, how it fails to do so in the economic participation of people. For example, take agricultural markets. In most of Africa, these are dominated by small-scale farmers, with only one or two economies as exceptions. Anyone who has worked with small-scale farmers knows the challenges they face. At the production level, their holdings are often fragmented, making it impossible to achieve economies of scale.

When it comes to markets, they don’t behave in the way economic theory would predict. Their market behaviour is unique. Some might call it unorthodox and understanding it requires a closer look at what they actually do.

Because of these and other challenges, I have turned to interdisciplinary approaches to understand the relationship between law and markets. This approach has led me into in-depth qualitative research: studying how farmers behave, how governments design agricultural policies, what assumptions are made about these actors, and what assumptions law itself makes when it talks about market facilitation or regulation. And then: how do these assumptions help or hinder inclusion?

Within that framework, I have explored various areas of law and the economy. Another interest of mine is informal economic activity, which is widespread in Africa. In almost any African city, you will find street vendors, most of them operating outside the law. Governments rarely enforce prohibitions against them, partly because such enforcement can lead to violence. So, they tend to tolerate it.

Anyway, I should not take centre stage. What else do you want to know? You have got me into an academic mood, so I could just keep talking.

That is good! How did you end up here? What is your connection to the Chair of African Legal Studies? And what shared academic interests do you have?

When the Chair announced this event, the focus areas caught my attention. One example is legal consciousness, which, in simple terms, is about how people interact with law and legal systems. I submitted a paper related to that because I think there is very little research on this in Africa, and it is important. It can deepen our understanding and perhaps explain phenomena like the high levels of oligopolism in Africa.

For instance, in Malawi where I am m from, there were significant reforms to land laws. For the first time, customary land (land acquired or inherited through custom) was regulated. This is important because over 80% of land in Malawi falls into that category. And it is not unique to Malawi; most sub-Saharan countries have similar arrangements.

Yet, despite the reforms, many communities continue to act as if they never happened. In some areas, people are outright hostile to the new laws. To them, state law is irrelevant compared to cultural norms, which they see as more important.

This raises serious questions about how we think about law in sub-Saharan Africa – why reforms fail, and whether the solutions we propose are even fit for purpose. Resistance to reforms suggests they often are not. I want to see more research that can help design solutions that genuinely improve inclusion and the well-being of everyone.

So, at this point, is it about raising awareness, or is it already about encouraging more research?

It is about encouraging more research. In Africa, much of the law responds to the demands of professional legal practice, but at a scholarly level, we do not focus enough on social problems and the role of law in them. Some reforms are simply legal transplants from elsewhere, assuming they will work in Africa too, which is risky.

There is also data from surveys like Afrobarometer. One recent survey showed that, in some West African countries, undemocratic military governments are more popular than democracy. That points to dissatisfaction with legal reforms that alienate people by ignoring their lived realities and expectations.

As scholars, we should dig deeper: Why do people feel this way? What can we learn from them? Through qualitative methods like interviews, ethnography, and observation, we could better understand what seems like a paradox: people rejecting democracy because they feel past governments – though undemocratic – served them better.

Is your research focusing on specific regions in Africa?

For my PhD, I focused on Malawi. But I have realized that, while every African country has its history, there are common themes – especially in sub-Saharan Africa, shaped by colonial legacies. Lessons from one country can often be useful for understanding another.

Are there African states that are more advanced in terms of legal consciousness?

“Advanced” might not be the right word. But some countries are relatively stable – like Botswana, which has a strong economy and stable democracy. If more African countries were like Botswana, the continent might be in a better place.

South Africa is unique – it still faces challenges from its long history of economic and political exclusion, and the dust hasn’t fully settled. Mauritius is another example: ethnically homogeneous, island-based, quite advanced – but very different from the large and diverse countries of sub-Saharan Africa.

In bigger states, challenges tend to multiply. And one problem is that we don’t always learn enough from our challenges before moving forward.

And when we tie this to the conference, what role can conferences like this play?

They’re crucial. Conferences like this allow African scholars to engage deeply with each other on challenges, potential solutions, and ways to share our research outputs.

We can develop solutions that grow from within the continent, for the continent rather than importing ideas wholesale. This particular conference, with its theme “Law and Belonging as Relational Practices,” is especially relevant to issues of exclusion, inclusion, and dissatisfaction with the law itself.

Ideally, such conversations should continue – perhaps even be institutionalized through scholarly publications or other platforms, creating a strong niche in global legal scholarship.

One final question: younger scholars might read this interview. What’s your advice to them?

Find innovative ways to study Africa’s challenges. Furthermore, interdisciplinary approaches are especially valuable. Traditional legal approaches have their uses, but they are limited. Look at law in its broader social context: how it works, where it fails, and why. This perspective can lead to richer, more relevant scholarship and perhaps better solutions.

Thanks a lot. It was a great interview.

Oh, really? I hope so. I was trying not to talk too much.

No, it was great. We have some excellent material for the blog.