ANALYSIS John Yajalin 8 April 2022

Introduction

On the 22nd of November, 2021, myjoyonline.com carried a sensational headline: “We are tasked to buy motorbikes and iPhones for our husbands after years of working– Kayaye Association President”.[1] Even though the story might sound absurd and hyperbolic, the complaint by the Kayayei Association’s president has some truth. My research on north-south migration in Ghana has revealed that females have become leading players in north-south migration within the country and “carry the burden” of remitting to take care of their families.

In this short article, I argue that female migrants, commonly known as “kayayei,” “carry the family burden” of providing for themselves and remitting to take care of their families back home. In my estimation, this is a paradox since traditionally, females in northern Ghana are supposed to be homemakers, being provided for and not the other way round. The essay is structured as follows. The subsequent section following the introduction gives a brief background about the Kayayei, followed by a re-examination of the migration question, with a specific interest in north-south migration in Ghana. The final section is the concluding remarks.

Who are the Kayayei?

The kayayei are female head porters who mostly operate in large markets in Ghana by carrying loads for customers for a fee. The loads or goods are often carried on their heads. The concept “kayayei” comprises two words, “Kaya”, meaning a load from the Hausa language, while “yei” (plural), meaning girls or females, or “yoo” (singular) from the Ga language spoken mainly in Accra.[3] The kayayei are mainly young girls who migrate from the northern part of Ghana to the cities of Accra and Kumasi in the south.

Revisiting the Migration Question

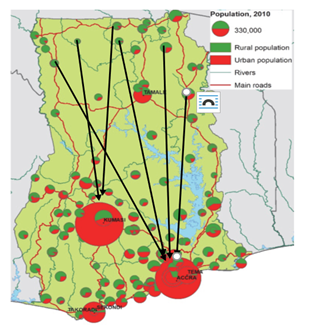

Migration is defined by the International Organization for Migration as the movement of people regardless of the distance across an administrative or international border beyond six months.[4] While the Covid 19 pandemic appears to have slowed down international mobilities due to the closure of state borders, migration within countries continues to surge.[5] Today, there are over one billion migrants worldwide, with only 281 million being international migrants meaning that the remaining estimated 719 million are migrants within countries.[6] In Sub-Saharan Africa, internal migration is the most prevalent and accounts for the unprecedented urbanization in the sub-region.[7] Internal migration in Ghana appears to mirror the trend in Sub-Saharan Africa, with north-south migration being the dominant phenomenon. North-south migration in Ghana refers to the temporary or permanent relocation of people from the north to the south.[8]

The phenomenon has a long history dating to the colonial era. In those days, the northern protectorate, as the colonialists called it, was mainly used as a labor basket to feed the cocoa plantations and gold mines in the south since the northern enclave lacked natural resources such as gold and timber.[11] After more than 60 years of independence, the phenomenon continues unabated and intensified. In the colonial and early independence eras, females were not active participants. Only abled adult men migrated. Although there were instances in which women migrated, they moved along with men and other family members. However, recent studies have shown that young females now dominate the phenomenon in what can be termed “the feminization” of the north-south migration in Ghana.

What Accounts for the current north-south migration patterns in Ghana?

Studies show that push-pull factors propel the phenomenon.[12] In a focus group discussion with the leadership of the Kayayei Association in Accra, discussants asserted that the opportunities available in the market centers in the south mostly attracted them.

For me, the kaya business is good. It is better to be a kayayoo than be unemployed and reliant on others. There is no work up there in the north, but there are many large markets here, and we can help people who shop by carrying their goods for them in these crowded markets. We help customers with their loads when they purchase goods from the shop. It is risky work as you have to go through trucks and vehicles in making your way around. I sleep outside in the open. We do it because there are no alternatives for us. We have to save and send money back to take care of our family needs. Some of us, our husbands, agreed for us to come. As you can see, most are very young, and some have completed Junior High and Senior High schools

Text Box: Focus Group Discussion with the Kayayei (Source: Author’s field survey, June 2020)

The discussants’ views revealed that the large commercial markets and domestic work opportunities in the south offered economic benefits largely unavailable in the areas of origin. The findings validate previous studies that the developmental disparities between the north and south of Ghana account for the north-south migration. Of keen interest in this article is that most discussants’ decisions to migrate were family decisions in which they were to remit to help take care of the family needs, as alluded by some of the discussants.

Concluding Remarks

The article demonstrated with primary and secondary data that females have not only become active participants in north-south migration in Ghana, but they now “carry the burden” of providing for their families through remittances, a somewhat paradoxical practice. While the kayayei believe that their move is rewarding, the nature of their job has profound health implications. Besides, they live under precarious conditions and sleep in the open without proper accommodation. The recommendation in this rather short piece is that there is the need for stakeholders such as the Imams, the chiefs, and Church leaders in sending communities to have a critical discussion of the increasing “kayayei” phenomenon.

[1] Ayisha Akua Ibrahim, ‘We Are Tasked to Buy Motorbikes and IPhones for Our Husbands after Years of Working – Kayaye Association President’ Myjoyonline.com (Ghana, 2021) <https://www.myjoyonline.com/we-are-tasked-to-buy-motorbikes-and-iphones-for-our-husbands-after-years-of-working-kayaye-association-president/>.

[2] Eugene Osei-Tutu, ‘The Kayayee Conundrum; A Situation That Requires Urgent Fixing’ Modernghana.com (Ghana, 2020) <https://www.modernghana.com/news/1031151/the-kayayee-conundrum-a-situation-that-requires.html>.

[3] A. M. Oberhauser and M. A. Yeboah, ‘Heavy burdens: Gendered livelihood strategies of porters in Accra, Ghana’ [2011] Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 22, 32; M. A. Yeboah, ‘Gender and livelihoods: Mapping the economic strategies of porters in Accra, Ghana’ [2008] West Virginia University.

[4] International Organization for Migration, ‘Glossary on Migration 2nd Edition’ <https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml25_1.pdf>.

[5] United Nations, ‘International Migration 2020 Highlights’ <https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/news/international-migration-2020>.

[6] Guglielmo Schininá and Thomas Eliyahu Zanghellini, ‘Internal and International Migration and Its Impact on the Mental Health of Migrants’ in Driss Moussaoui and others (eds), Mental Health, Mental Illness and Migration (Springer Singapore 2021) <https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-10-2366-8_3> accessed 29 March 2022.

[7] Cecilia Tacoli, Gordon McGranahan and David Satterthwaite, Urbanisation, Rural-Urban Migration and Urban Poverty (JSTOR 2015).

[8] Mariama Awumbila, ‘Drivers of Migration and Urbanization in Africa: Key Trends and Issues’ (2017) 7 International Migration; Mariama Awumbila, ‘Women Moving within Borders: Gender and Internal Migration Dynamics in Ghana’ (2015) 7 Ghana Journal of Geography 132.

[10] World Bank World Bank, Rising through Cities in Ghana: Ghana Urbanization Review Overview Report (2015).

[11] EA Ofosu-Mensah and J Agyei, ‘Historical Overview of Internal Migration in Ghana’. http://197.255.68.203/handle/123456789/2198

[12] Thomas Antwi Bosiakoh and others, ‘The Dynamics of North-South Migration in Ghana: Perspectives of Nandom Migrants in Accra’ (2014) 2 Ghanaian Journal of Economics 97 <https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC169144> accessed 18 March 2022; Razak Jaha Imoro, ‘North-South Migration and Problems of Migrant Traders in Agbogbloshie’ (2017) 3 African Human Mobility Review; SO Kwankye and others, ‘Independent North-South Child Migration in Ghana: The Decision Making Process’ [2009] Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalisation and Poverty, University of Sussex Working Paper T-29; Mariama Awumbila and Gertrude Dzifah Torvikeh, ‘Women on the Move: A Historical Analysis of Female Migration in Ghana’ [2018] Migration in a globalizing world: Perspectives from Ghana 171.

2 replies on ““Carrying the Family Burden”: The Paradox of the Kayayei Migrants in Ghana”

Indeed, the leadership of religious groups and traditional leaders in sending communities should be involved such discussions. There is definitely the need for them to understand the context at the destination. This may assist in managing the demands made by spouses and the family

To know that these potters are “TASKED” to buy a motorbike and iPhone for their husbands is unbelievable and unrealistic.

And who at all made this task for them