ANALYSIS Prof. Dr Bernd Kannowski 11 February 2022

Black history is a history of struggles for freedom. Today, we are still fighting structural racism and everyday discrimination. A few decades ago, it was the fight for civil rights and the fight against apartheid. A step even further back into history, we remember the struggle for liberalisation from colonialism and the founding of new states. And if we go less than 100 years back in time, it was the fight against slavery.

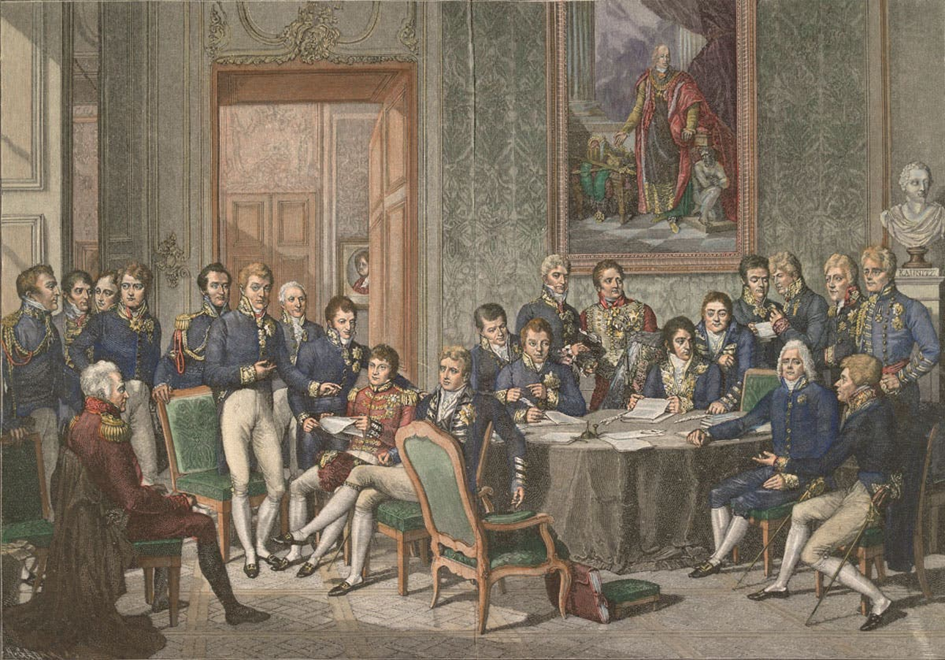

Designing Europe’s Future

The Congress of Vienna of 1814-1815, is a historical event of European, if not global, significance. The Congress of Vienna is a milestone for the territorial and governmental organisation, but by no means merely for the German one. The question at stake was whether a united Germany as a nation state should emerge at all after the shocks of the Napoleonic wars. As is well known, the state representatives gathered in the Austrian capital were unable to agree upon this, so only a loose confederation of states called the “German Confederation” (Deutscher Bund) came into being.

Even though the result was not the emergence of Germany as a nation state, it is clear that international law was at stake. This had already been made clear by the terminology: the German Confederation characterised itself as an “association under international law” (völkerrechtlicher Verein).[1] Thus, we know the Congress of Vienna as a multinational assembly of a proportion previously unknown that was concerned with the new order of peace in Europe. As far as its major goals are concerned, it can probably also be said that the Congress of Vienna was principally successful. But that is not of my concern in this blog piece. I am concerned with an aspect that has received little attention among historians.[2] . This may have to do with the fact that it is by no means on the main list of issues that were negotiated at the Congress of Vienna. It rather appears quite alien compared to the things typically discussed in Vienna in those days.

Declaration against Slave Trade

Besides the territorial restructuring of Europe, the representatives discussed the ending of international slave trade. It is commonly referred to as the Declaration against the Slave Trade and formally known as Declaration … concerning the Abolition of the African Negro Trade or the Slave Trade[3]. It was unanimously adopted by the eight signatories of the Congress of Vienna[4] on 8 February 1815. The eminent historian Heinz Duchhardt in the prestigious Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law, says of this very Declaration: “Indeed, it was the first time that human rights were guaranteed by international law.”[5] If we consider what international law means on the one hand and what human rights mean on the other (from a historical perspective), I think there can be no denying that Duchhardt is right in this classification.

Human Rights entering International Law

It is comparatively easy to say what international law is. It is supranational law, i.e. law that exceeds the scope of national government’s authority. What human rights are supposed to be from a historical perspective is much harder to say. A starting point could be today’s concept of human rights. As is well known, there is no international consensus on their exact content.[6] This question is so difficult to answer that efforts by the United Nations to define a smallest common denominator of human rights have repeatedly failed and may never succeed. It is known to be an extremely delicate question, so profoundly connected with ideological and religious aspects that it seems more sensible not to open this can of worms. A position which could command general assent is that slavery and slave trade is a direct violation of human rights. To a certain degree this was also true for the time around 1815, as is demonstrated by the French prohibition of slavery in its 1795 constitution[7] as well as by the British abolitionists. Consequently, what has been pronounced in Vienna in 1815 does not only have a clear human rights content, but it also demonstrates the first explicit appearance of human rights in international law.. Further, the document can be regarded as a milestone in Black Legal History as this . legal act concerns the trade in black people from Africa, who were referred to as “negroes” according to the derogative and meanwhile outdated terminology of the time.

Great Britain – The Driver for Abolitionism?

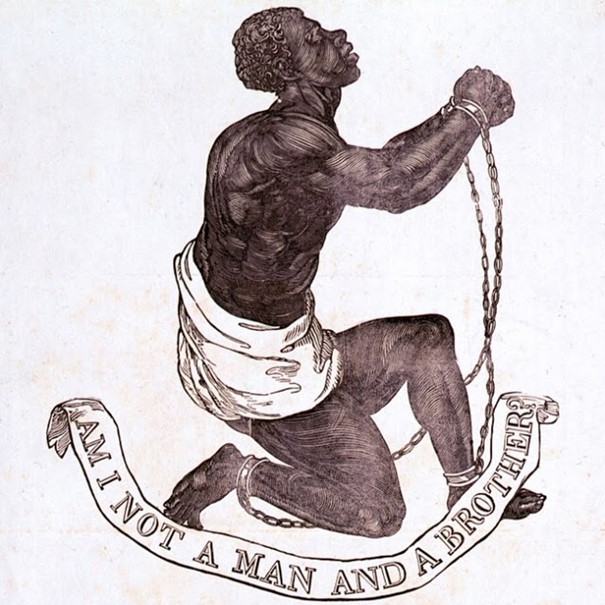

Great Britain may be described as the country abolitionism originated from above all others. Mainly for humanitarian reasons, demands for the abolition of slavery as it applied exclusively to Black people grew louder and louder, at which the Quakers played a primary role.

The simple and poignant depiction of a black slave in chains with the words “Am I not a man and a brother?” gained fame through medallions, mass-produced by the English industrialist and staunch anti-slavery activist Josiah Wedgwood in the 18th century.[8]

It is however important to note that slavery, with its ugly face, was never something that was seen in the British motherland. The abduction of people from Africa for the purpose of forced labour in conditions that many did not survive for long was always a colonial phenomenon.

The shipments of enslaved people were to the so-called New World, not to Britain. There is a famous 18th century decision by Lord Mansfield that slavery was against British law and that a slave entering British soil should be set free.[9] But this exclusively referred to British soil and had no impact on the legal situation in the colonies. In a perfidious way, it is similar to today: working conditions that are unworthy of human beings, wages that are unimaginably low in our Western eyes, destruction of the environment through chemicals that are banned in our countries and all the human misery that goes with it are not European phenomena either.

When Great Britain ultimately lost its North American colonies in the memorable year of 1776, slavery logically also lost all its significance for the British Empire. The situation was different – as bizarre as it may seem – for a state (or rather a union of states) that had taken up the cause of human rights in a very special way. In any case, the British could now easily afford to do without slavery. In 1807, Great Britain was one of the first countries to ban the trade in Black slaves.[10] Of course, this was not yet a ban on slavery itself. But it was an important step towards its end and ultimately heralded it. In this way, the British put a stop to new abductions of people. And as we all know, the British were not exactly insignificant on the seven seas in those days. None other than Napoleon had to learn this painfully, much to his annoyance.

The ban on the slave trade had one great downside for the British. It put them at a competitive disadvantage vis-à-vis other European colonial powers. If some nations – such as Portugal and Spain in particular – continued to engage in this lucrative business, this meant that the British had to forego their share of the cake. Of course, this could only be eliminated if the cake itself disappeared altogether. It is a similar phenomenon as today with measures against climate change or a ban on nuclear power plants. The result is that it is much less effective, if not completely pointless, unless everyone joins in. Furthermore, a declaration against the slave trade was important for the British because under martial law they could easily bring up slave ships and thus suppress trade. Now that peace had prevailed after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, this was no longer possible under international law.[11]

Adopting a Declaration vs. Signing a Treaty

Thus, not only humanitarian but also economic considerations may have been behind the British approaching the other signatories at the Congress of Vienna with the proposal to adopt an international ban on the slave trade. For the reasons just described, the profiteers were not exactly enthusiastic about this proposal. With diplomatic skill, however, the British finally succeeded in getting all eight powers to sign a declaration to this effect. This was deliberately called a “declaration” and not an “agreement” or even a “treaty”. It was not a treaty, which means that the document had no binding effect. The signatories only set themselves the goal of working towards an end to the slave trade. The declaration explicitly states that no time horizon should be given for the abolition of slavery.[12]

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to deny the importance of the document for this reason. As is well known, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 is neither legally binding as an international treaty nor does it have a time dimension for the realisation of human rights in the national legal systems of the signatory states. Nevertheless, the impact of this very Declaration is – which no one will deny – enormous. For this reason, the 133 years older document that I have briefly presented in this article should be given the importance it deserves. Finally, I would like to quote a few passages from it in English translation. The original is in French, the lingua franca of the diplomatic world at the time.

“In bringing this declaration to the knowledge of Europe and of all the civilized nations of the earth, the said plenipotentiaries are convinced to encourage all other governments, and in particular those which, by abolishing the slave trade, have already shown the same sentiments, to support them with their suffrage in a cause whose final triumph will be one of the most beautiful monuments of the century which has embraced it and which will have brought it to a glorious conclusion.”[13]

[1] Art. 1 Wiener Schlussakte (http://www.documentarchiv.de/nzjh/wschlakte.html).

[2] Helmut Berding, Die Ächtung des Sklavenhandels auf dem Wiener Kongress 1814/1815, HZ 219 (1974), pp. 265-289 (265s.).

[3] Déclaration … relativement à l’abolition de la traite des nègres d’Afrique ou du commerce des esclaves. To be found in Johann Ludwig Klüber (ed.), Acten des Wiener Congresses in den Jahren 1814 und 1815, vol. 8, Erlangen 1818, Acten betreffend die Abschaffung des Neger- oder afrikanischen Sklavenhandels, pp. 3-53.

[4] Austria, Russia, United Kingdom, Prussia, France, Spain, Portugal and Sweden.

[5] Heinz Duchhardt, From the Peace of Westphalia to the Congress of Vienna, in: Bardo Fassbender / Anne Peters (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of International Law, Oxford 2014, pp. 628-653 (650).

[6] Tom Bingham, The Rule of Law, London 2011, p. 68.

[7] Art. 15: „Tout homme peut engager son temps et ses services ; mais il ne peut se vendre ni être vendu ; sa personne n’est pas une propriété aliénable.“ https://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/les-constitutions-dans-l-histoire/constitution-du-5-fructidor-an-iii.

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josiah_Wedgwood.

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Somerset_v_Stewart.

[10] Denmark was the first slave-trading nation to ban slavery across the Atlantic in 1803.

[11] Randall Lesaffer, Vienna and the Abolition of the Slave Trade, https://opil.ouplaw.com/page/498.

[12] „[L]es dits plénipotentiaires reconnaissent … que cette déclaration générale ne saurait préjuger le terme que chaque puissance en par ticulier pourrait envisager comme le plus convenable pour l’abolition définitive du commerce des nègres. Par conséquent la détermination de l’époque , où ce commerce doit universellement cesser, sera un objet de négociation entre les puissances …“.

[13] „En portant cette déclaration à la connaissance de l’Europe , et de toutes les nations civilisées de la terre , les dits plénipotentiaires se flattent d’en gager tous les autres gouvernemens , et notamment ceux qui en abolissant la traite des nègres , ont manifesté déjà les mêmes sentimens , à les appuyer de leur suffrage dans une cause dont le triomphe final sera un des plus beaux monumens du siècle qui l’a embrassée et qui l’aura glorieusement terminée.“