ANALYSIS René Brosius 25 June 2021

In the inner-Somali discussion, the term “4.5 system” comes up again and again, and for outsiders it is not easily recognisable what concept lies behind this terminology Therefore, I want to offer a brief explanation to keep up with the ongoing developments.

The 4.5-system is a mechanism for sharing political power, a quota system, so to speak. The logic of proportional representation goes back to the question of where Somalis actually come from. A powerful question with no easy answer to it. History is not help either, the nomadic culture has left us neither writings nor many buildings on the basis of which we could draw conclusions about the life and early society of the Somalis. Nevertheless, the Somalis were long considered one of the most homogeneous peoples in Africa. A common tribal system, which gives every Somali an identification code of his or her patriarchal descent at birth, society dominated by the common Islamic belief and the common language, rounded off this impression. To some extent, however, this picture has to be corrected.

The Question on the Origin of Somalis

Despite numerous scientific studies, the question of the Somalis’ origin has not yet been conclusively clarified. Two narratives dominate the debate. The first emphasises the Arab influence in the development, while the second one stress the African roots of the “proto-Somali”, as the cradle of Somali identity.

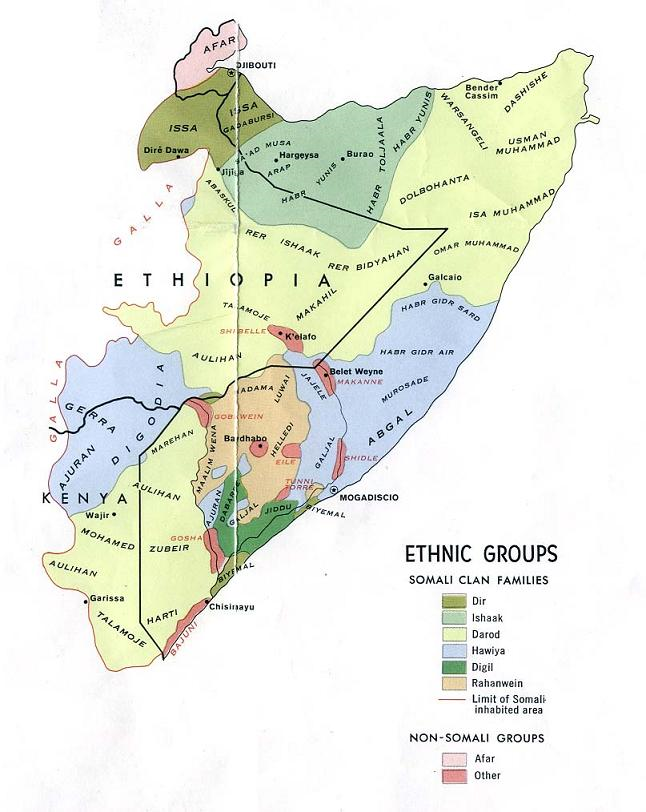

Somalia has a socially dominant tribal system, which can first be divided into the categories of “nomadic” and “sedentary”. The sedentary groups include the Digil-Mirifle and the Rahanweyn. Both lifestyles are traditionally based on agro-nomadism onthe fertile banks of the Shabelle and Jubba rivers. The Rahanweyn are composed of a variety of different influences, including descendants of other Somali tribes, but also Oromos and East African Bantu. The Digil-Mirifle are more homogeneously composed and are derived from migrated and newly emerged clan groups. Collectively, they are referred to as Sab, after their common progenitor. The Hawiye, Dir and Darood have more of a nomadic character and have settled in the northern region. The Isaaq are often counted separately among them. Strictly speaking, however, they are derived from the Dir. These clan groups are called Samaale after their progenitor. Sab and Samaale are considered “noble” tribes. At least the Samaale also link their lineage to Arab tribal fathers. Not infrequently, this is accompanied by references to a family proximity to the Prophet Mohammed (PBUH).

African Origin, African Perspectives

Representatives of the African perspective, on the other hand, emphasise less the Arab and more the African roots. According to them, the actual settlement of the Somali peninsula did not take place only from north to south, after the link with Arab immigrants, but much earlier. Bantu and Oromo groups are said to have migrated from mountainous areas of present-day Ethiopia and from the south and settled on the banks of the Jubba and Shabelle rivers, thus forming the “proto-Somalis”. Only later did migration towards the north take place and then, from the 11th century onwards, a renewed (return) migration of northern, meanwhile Islamised and Arabised Somalis took place in various waves. The return migration was accompanied by the subjugation and displacement of the Somali population. The strict descent system meant that there was no longer any real mixing, but a widely ramified, Arab-Somali clan system was established. The non-displaced Bantu/Oromo groups, who in contrast to the Arab-Somali immigrants have black African physical characteristics, were integrated into the clan system at a low social level and socially “Somalised”. To this day, however, there are distinctions based on these physical characteristics. Thus, the black African minorities are also called “Jareer” (“wirehaired”).

In addition to these clan structures, there are other social groups. For centuries, the Somali peninsula was a centre of the slave trade. From the coasts, slaves were taken mainly to the Arab world, Persia or India, and sometimes also to Egypt and Europe. It was not until the early 19th century that slaves were also increasingly used in the agricultural areas of southern Somalia. At times, the proportion of slaves in the population there is said to have been between 10 and 20 percent. In the course of colonisation, many slaves were released into freedom. A large number of them emigrated, but some remained, especially in the southwest and south of present-day Somalia.

If you superimpose these roughly outlined developments, the picture changes from a homogeneous to a diverse and multi-ethnic society. In addition, there are a number of smaller migrant groups who are descendants of former Persian, Yemeni or, to some extent, Italian and Portuguese immigrants. Mogadishu, for example, was founded by Persian traders between the 8th and 9th centuries. Among the best-known minorities are still the Reer Xamar, who refer to these founding fathers. They still live in Mogadishu, are culturally largely “Somalised” and live relatively concentrated in the “Xamarweyne” district.

What does all this have to do with 4.5?

One of the key questions after the civil war was how to distribute power in the country in the future. After several peace and reconciliation conferences, a power-sharing formula was first agreed at the Arta Conference in Djibouti (2000), and later in Mbagathi, Kenya (2002-04). A mechanism was agreed to share parliamentary seats in the transitional parliament according to clan proportion. The “4.5 formula” was born. Of the total 245 seats, 49 seats each were to go to the four largest tribes, the Darood, Dir/Isaaq, Hawiye and Rahanweyn/Digil-Mirifle. 29 seats were to go to the “minorities” together, which was about half of the seats of any of the major clans. Hence the designation “.5” 25 more seats (about 10 per cent of the total parliament) were to be reserved for women. 5 each from the major clans and another 5 from the “minorities” group. This formula, also due to the lack of other political size units such as parties or election results, increasingly became key for the distribution of power at different political levels. The election of the future parliament is also to be essentially composed according to this key, with the proportion of women rising to 30 per cent.

Criticism is also linked to this. For the accusation is that the 4.5 system not only pursues the goals of political stability, but is also used for professional, social and political exclusion. The formula pushes minorities in Somalia into a “0.5” “caste” and thus also marginalises them socially and politically. But it is not that simple. The 4.5 formula is ultimately a reflection of historical social conditions. It only reflects what is socially present anyway. For example, marriages between “nobles” and representatives of the “.5” groups are not welcome and physically demanding professions are mainly practised by members of the “.5” families. But this also does not support the fight against inequality, but rather perpetuates existing structures of exclusion. Therefore, overcoming this provisional regulation is one of the most important goals for the near future.

3 replies on “The 4.5 System – An Instrument of Exclusion?”

I believe that because of the 4.5 system, the.5 minority clans support al-shahaab because they face discrimination and feel oppressed by the federal government. I am Somali, and I have always heard that the federal government in Somalia does not provide justice or essential support to minority clans, and that the bulk of people live in rural areas based on their clan. Because of the 4.5 system, I believe it is one of the main causes of al Shabaab’s continued popularity among the public.

Al-shabab stronghold is usually in galmudug region which is occupied by the major clans. And the reason they still are able to operate is due to the fact that many somalis will turn a blind eye if on of their relative is a member who murders people,coz they always prioritise qabil then deen

Both of the so called African and Arab perspectives when it comes to the origins of Somalis is utterly false and fraught with errors.

First off, Somali clans aren’t divided between “nomadic” and “sedentary” lifestyles, all clans practiced a mix of urban, agricultural and pastoralist occupations that dominated all of Greater Somalia and so it wasn’t exclusive to a certain region or clan. This is see from the fact that the Somali peninsula is dotted by ruins of numerous stone towns and civilizations in the coast and interior This overly simplistic analysis overshadows the complex history and culture of Somali society/civilization into this binary system of nomadic/sedentary.

Second, Rahanweyn and Digil-Mirifile (D&G) are two names for the exact same clan, they are used interchangeably, but perhaps most erroneously of all is the claim that D&G have influences from Bantus and Oromos when neither of those groups were in Southern Somalia in the Middle Ages. The Jubba and Shabelle were historically dominated and populated by Somalis with no archeological, linguistic or genetic evidence of a predessor group. The Bantu migrations stopped just south of NFD (Eastern Kenya) while the Oromo migrations would only first take place in the 16th century that saw them expand into Central/Eastern Ethiopia but not into Southern Somalia. DNA evidence of course further debunks this Oromo + Bantu = Proto-Somali theory since Somalis have virtually zero Bantu and Oromo DNA. Although there isn’t much research done in the origins of Somalis, it can be strongly hypothesized that proto-Somalis are descendants of lowland Eastern Cushitic groups that migrated to northern Somalia before migrating further south and populating the rest of the peninsula. The Saho and Afar who are also apart of the same language family have similar origins while Oromos diverged elsewhere and migrated to Ethiopia and Kenya instead.

There of course was also no migrations from so called Arabized Somalis that subjugated other Somalis. Islam spread from the north through trade and not warfare or violence. No caste or “descent system” was ever made because all Somalis were and still are ethnically and culturally homogenous. At best there were some marginalized clans like the Tumaal and Madhiban who were discriminated against but this is due to their occupations and not their lineage/ancestry, and such discrimination against blacksmiths can be seen in other Cushitic cultures as well. Also once again, there were no Oromos and Bantus in Somalia so none were integrated into Somali clans. In the current day, “jareer” refers to Bantu minorities that are descendants of slaves during the 19th century but by and largely are separate from the Somali clan system.

And lastly the idea that migrants from the Middle East founded Mogadishu is false and rooted in colonial era myth spouted by scholars like Enrico Cerulli and I.M Lewis who used fabricated texts like the Kitab al Zinuj. Archeological, oral and written evidence proves that Mogadishu was founded by Somalis and that Arabs, Persians and Indians only later came in as merchants and settled into their own quarters under the rule of Somali sultans. Those groups would mix with some of the local Somalis and their descendants are now known as Reer Xamar or Benadiris who are the only ones to claim to have founded Mogadishu.