Introduction

Gender-based violence (GBV) is a global epidemic that continues to devastate lives, particularly those of women and children. Despite numerous campaigns, policy frameworks, and international initiatives, GBV remains a global problem affecting many people’s lives. The 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence is an effort to amplify calls for action, raise awareness, and demand accountability for all stakeholders involved, including governments, to be accountable for the commitments that they made through international conventions in the fight against GBV.[1] Yet, since the time when the UN General Assembly designated November 25 as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, the number of women and girls at risk of violence seems to be escalating.[2] This situation warrants investigating why GBV persists and how we can reimagine our approach to create meaningful change.

Roots causes of GBV

At its core, GBV thrives in systems characterised by power imbalances. Across many African societies, if not the whole world, patriarchal structures dictate our ways of life in all walks of life, including social, economic, and political norms.[3] Such norms are not only institutionalised but also perpetuate toxic masculinities, where male dominance is celebrated, and female subordination is normalised by both men and women, intentionally or unintentionally. Across the world, women and girls continue being regarded as inferior subordinates to men and are at the disposable pleasure of men.[4]

It has also been a widespread phenomenon that women’s economic dependency is a significant factor weighing down many women and children to remain trapped in abusive situations. Many times, a lot of GBV survivors are conflicted between making an emotional decision and making an almost impossible financial decision to leave their abuser. This, coupled with limited access to education, employment, and economic independence, proliferates the vulnerability of women and children.

Furthermore, one would not fail to notice that in our societies, there are countless programs aimed at “empowering women” that fail to challenge the structural forces enabling male privilege. It is without a doubt that if these patriarchal systems are not addressed, empowerment efforts will remain superficial, and women will continue to be treated unfairly in our societies. Besides, some of these root causes of GBV extend deep into cultural norms and institutional practices, yet, many interventions merely scratch the surface without really challenging the deep-rooted and sometimes sanctioned cultural and structural causes of the problem.

Where does the 16 Days Campaign fall short?

The 16 Days of Activism is undoubtedly a powerful initiative. Since its inception, it has made strides in mobilising millions of stakeholders to raise awareness, advocate for survivors, and demand government accountability, among countless success stories worthy of celebration. But as we reflect on its impact, a pressing question arises: why, despite decades of activism, does GBV remain rampant, particularly towards underprivileged women and children?

One key issue lies in the campaign’s occasional nature intensified within the designated sixteen days. This focus on a concentrated 16-day period risks creating a “performative activism” culture. Undoubtedly, stakeholders often pour resources into events and social media campaigns, only to retreat into silence once the campaign concludes. This stop-start approach undermines sustained efforts to address GBV throughout the year. Even so, it is most likely that most stakeholders are hesitant to effortlessly support anti-GBV campaigns that seem untimely and not well aligned to these internationally recognised days.

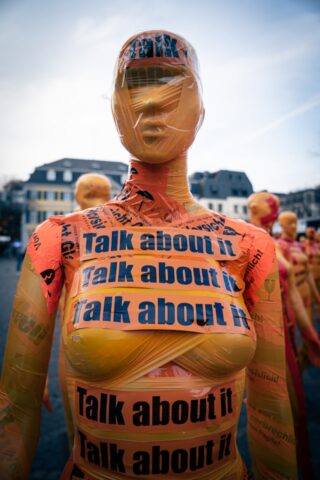

Moreover, many interventions during the 16 Days are isolated and selective, targeting symptoms rather than the systemic causes of GBV. For example, while shelter provision and survivor support are critical, these efforts do not address the cultural and economic factors that perpetuate abuse. While promotional materials in orange, purple, blue and rainbow colours usually brighten the events and help raise awareness, they fall short of bringing behaviour change in both victims and perpetrators. In essence, these piecemeal approaches fail to disrupt the larger systems that normalise and enable violence to its core.

What model can work?

Ending GBV requires a paradigm shift that moves beyond isolated events and embraces a sustained, systemic approach. While a one-size-fits-all approach is not ideal, a model that addresses some root causes might fit the purpose and bring about meaningful change. Such a model might include:

Governments and private sectors invest in programs that equip women with financial independence. Such programmes might include expanding access to education, creating equitable job opportunities, and supporting female entrepreneurs. These approaches recognise that economic empowerment is not a luxury for women and children affected by GBV but a necessity for reducing the vice.

This model must also recognise that efforts to end GBV must begin early, challenging toxic masculinity and gender stereotypes in schools and even outside the classroom walls. Such an initiative might entail comprehensive gender education rooted in local contexts that can help shift harmful attitudes. These initiatives can possibly engage communities, religious institutions, and cultural leaders who also have a crucial role in reshaping these adverse social norms. Obviously, such programs would create meaningful changes if they were not limited by time and resources designated for a specific period of the year.

Furthermore, a model that strengthens and enforces laws against GBV is critical.[5] However, this must recognise that laws are meaningless without proper implementation. Therefore, it will be practical for governments to allocate resources for legal aid, survivor protection, and training for law enforcement to handle GBV cases sensitively. Such sensitivity can also involve empowering community structures and institutions to apply laws and social orders that promote the rights and freedoms of women and children while safeguarding the human rights of all people in the communities.

Ideally, it would also make a lot of sense to challenge the current gender parity in political and administrative representation of women at different levels.[6] While this goes back to dealing with negative gender stereotypes that do not value women representation in politics, one is a bit assured that women in decision making positions will advance a women’s agenda. This is where policy and legal frameworks are put in place to promote fairness, non-discrimination, transparency and removing barriers that prevent individual from participating in society due to their gender.

Relatedly, the approaches in this model must ensure that GBV survivors are at the heart of anti-GBV initiatives. It is evident that the experiences and insights solicited from GBV survivors can guide more effective interventions that are survivor-oriented but also culturally acceptable. Additionally, it goes without saying that such a model demands funding and support for grassroots organisations, which are often the first responders in crises.

Conclusion and Takeaways

So, while we reflect on this year’s 16 Days of Activism’s theme, “Towards Beijing +30: UNiTE to End Violence Against Women and Girls,” marking a pivotal moment after the Beijing Platform for Action, we must ask whether global commitments have translated into tangible change. At the same time, we must reflect on our government’s commitments towards addressing GBV in a more accountable manner while ensuring that resources towards addressing the vice are provided in a timely manner. Nevertheless, this commitment needs not to be a mere rehash of promises amplified during the 16 days of Activism, it must be a prioritised long-term investment in the fight against GBV programs and the promotion of gender equality.

[1] UN Women, Concept Note 2024: Towards 30 years of the Beijing Declaration and platform for action: Unite to end violence against women < https://unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2024-10/UNiTE_16%20Days_2024_Concept%20Note_final%20Oct4.pdf> accessed 26 November 2024.

[2] UN Women, Concept Note 2024: Towards 30 years of the Beijing Declaration and platform for action: Unite to end violence against women < https://unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2024-10/UNiTE_16%20Days_2024_Concept%20Note_final%20Oct4.pdf> accessed 26 November 2024.

[3] Iyanda, A.E., Boakye, K.A., Olowofeso, O.H., Lu, Y. and Salcido Giles, J., ‘Determinants of gender-based violence and its physiological effects among women in 12 African countries’ (2021) 36(21-22) Journal of interpersonal violence ) NP11800, NP 11813.

[4] Dube, E., 2023. The cultural distortion of the African world view and the subordination of women in ‘postcolonial’ African societies (2023) 42 (3) South African Journal of Philosophy 192,196.

[5] Ouedraogo, R. and Stenzel, M.D., ‘The heavy economic toll of gender-based violence: evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa’. (International Monetary Fund, Washington DC, USA 2021) 29.

[6] <https://www.cfr.org/article/womens-power-index> accessed 5 December 2024.