Intersectionality as a Key Concept for the Protection Against Multiple Discrimination

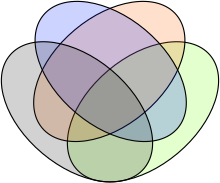

The concept of intersectionality takes into account the interpenetration of various identity categories like race, gender, class, sexuality and disability as well as the structural interlocking of multiple forms of oppression like racism, sexism, classism and heterosexism by using an analogy to traffic: “Discrimination, like traffic through an intersection, may flow in one direction, and it may flow in another. If an accident happens in an intersection, it can be caused by cars traveling from any number of directions and, sometimes, from all of them.”[i] Coined by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw as a critical reaction to judicial interpretations of anti-discrimination law in the field of employment practices in the United States, the allegory of a roadway has been firmly established for illustrating multiple forms of exclusion and subordination.

In her deliberations Kimberlé Crenshaw refers to the following legislative context and the related case in point: The Title VII of the US Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employment discrimination on the basis of “race, color, religion, sex and national origin.”[ii] With regard to this provision, she states that some judges consider each category as separate and mutually exclusive. Furthermore, she criticizes that the benchmarks for discrimination are based on the experiences of white women in respect of gender and black men in view of race. These misconceptions are well illustrated in the case of Emma DeGraffenreid v. General Motors (1976) where five Black women from St. Louis filed a lawsuit against the employment policy of the automotive manufacturer: Before 1964, the company did not employ Black women, but white women were involved in the administration and Black men were represented in the production. After a recession, all black women employed after 1970 lost their jobs due to the seniority system[iii] based on the principle ‘last hired – first fired‘.[iv] However, the District Court in Missouri rejected the suit in which the mentioned plaintiffs referred to a discrimination specifically as Black women[v] with the argument that “they should not be allowed to combine statutory remedies to create a new ‘super-remedy’ which would give them relief beyond what the drafters of the relevant statutes intended. Thus, this law suit must be examined to see if it states a cause of action for race discrimination, sex discrimination, or alternatively either, but not a combination of both.“[vi]

Since the last three decades, the concept of intersectionality has itself proved as an innovative analytical tool and powerful instrument in the struggle for social justice. However, the chosen metaphor is limited to only two dimensions of subordination and disenfranchisement. Furthermore, it cannot capture different levels of the scale of oppression nor does it consider specific features of each type of discrimination. Last but not least, the allegory of an intersection cast in concrete evokes a static imagination that misrepresents the fluid social reality, where changing social, political and economic conditions come along with shifts in discrimination practices.[vii]

Despite some weaknesses the ground-breaking concept of intersectionality allows to acknowledge compound discrimination and makes particularly vulnerable and marginalized groups visible. Having this in mind, the application of the concept shall not be limited to activists and scholars but must be established as an inherent feature in court rooms. Especially with reference to the court room, the promotion of the concept of intersectionality also means that state employment policies do not itself perpetuate multiple discrimination by prohibiting for example Muslim women to wear a headscarf in office and thereby denying them access to certain professions.[viii]

[i] Crenshaw, Kimberlé 1989: Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, Vol. 1989 (1), p. 149.

[ii] Title VII of the US Civil Rights Act of 1964, online available at https://oshr.nc.gov/media/1457/open.

[iii] Crenshaw, Kimberlé 1989: Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, Vol. 1989 (1), pp. 141ff.; See also Crenshaw, Kimberlé 2016: TedTalk. The urgency of intersectionality, online available at https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_intersectionality.

[iv]Auma, Maureen Maisha 2020: Intersektionale Gerechtigkeit und intersektionale Feminismen: Die Vielschichtigkeit und Überschneidung von Ausschlussprozessen. Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste, online available at https://www.asf-ev.de/de/infothek/themen/gender/intersektionale-gerechtigkeit/.

[v] For a pioneering contribution to black women’s studies see the anthology Hull, Akasha Gloria, Patricia Bell-Scott and Barbara Smith (eds.) 1982: All the Women are White, All the Blacks are Men, But some of us are Brave. New York: The Feminist Publisher.

[vi] DeGraffenreid v. General Motors, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri – 413 F. Supp. 142.

[vii] Harris, Angela and Zeus Leonardo 2018: Intersectionality, Race-Gender Subordination, and Education. Review of Research in Education Vol. 48, p. 6f.

[viii]For the prohibition of displaying religious and ideological symbols for officials in Germany see the draft bill “Gesetz zur Regelung des Erscheinungsbildes von Beamtinnen und Beamten sowie zur Änderung weiterer dienstrechtlicher Vorschriften“ online available at http://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/gesetzgebungsverfahren/DE/Downloads/kabinettsfassung/gesetz-zur-regelung-des-erscheinungsbildes-von-beamtinnen-und-beamten.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1

What Future for Article 3 (3) of the German Constitution?

Over more than a decade politicians, lawyers and activists controversially debate on the term race in the German Constitution. There, Article 3 (3) states that “no person shall be favoured or disfavoured because of sex, parentage, race, language, homeland and origin, faith or religious or political opinions. No person shall be disfavoured because of disability.”[1] Adopted in 1949 in the aftermath of World War II and the Holocaust, the wording of the Basic Law was chosen as a reaction to the racist ideology and the related genocide under the rule of the Nazi-regime propagating ideas of racial purity and racial superiority. Inspired by the famous phrase ‘Never Again!’ the Basic Law was installed as a bulwark against an inhuman and racist policy of extermination. However, the formulation of the prohibition of discrimination must be open to revision as social reality changes and new anti-discriminatory perspectives and voices become leading in the current discourse. Whereas the various actors are mostly united in the notion that ensuring equal treatment and preventing discrimination is indispensable, the answers to how to reach this goal are manifold.

One perspective stressing the equality of all humans postulates the deletion of the term without replacement as human races are no biological fact but merely a social construct. Or more precisely, the idea of human races is not the basis but the result of racism and thus deeply rooted in suppressive regimes like the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism. Therefore, retaining the term race in the Basic Law reproduces these segregating and hegemonic categories and patterns of thinking in Germany’s key legal document[2].

Another perspective taking into account differences, inequalities and hierarchies pleads for a reformulation of Article 3 (3). The argument behind this claim is that discrimination obviously exists, and racism is real. Cancelling the term race completely would misjudge the historical as well as the present context of racialized hate crime and practices of institutionalized racism. But how to rephrase the respective paragraph and simultaneously maintain the current level of protection? Frequently discussed alternatives include ethnicity or skin colour. However, the first term shifts the focus from racial marginalisation to discrimination based on culturalized affiliation. The second term creates the illusion that racism is primarily based on the biological feature of complexion and not part of a powerful and oppressive system. For pushing forward the debate the Ministry of Justice suggested in February 2021 to substitute race with ‘for racist reasons’.[3] But again, this reformulation weakens the level of protection as in this phrase racial discrimination is connected with the subjective element of intention.

A third perspective does not at all acknowledge a necessity for certain reforms and prefers the retention of the term race, as it can be found as an analytical legal term in many European and international treaties and documents including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[4] Furthermore, the term incorporates Germany’s historical legacy and compromises a constructivist dimension, similar to gender, that must be scrutinised. When already stressing that the term race does not reflect a biologically given fact it seems paradoxical to persist on the preservation of a misleading formulation.

For now, a final solution is not yet in sight and the royal road for balancing the endeavour to install equality and the need to recognize differences has not been found so far. A further obstacle emerges when considering that in order to change the constitution a two third majority in both houses of parliament is required. But as critical voices further gain pace it is overdue that deputies react to the views and claims of the citizens they represent and yield a constitutional change.

This short summary of the status quo on the reform efforts for Article 3 (3) of the German Basic Law is highly inspired by an article[5] written by Prof Maureen Maisha Auma.

[1] Niemand darf wegen seines Geschlechtes, seiner Abstammung, seiner Rasse, seiner Sprache, seiner Heimat und Herkunft, seines Glaubens, seiner religiösen oder politischen Anschauungen benachteiligt oder bevorzugt werden. Niemand darf wegen seiner Behinderung benachteiligt werden.

[2] See Prof. Maureen Maisha Auma for more

[3] Vorschlag des Justizministeriums. So soll „Rasse“ aus dem Grundgesetz verschwinden. Süddeutsche Zeitung, 02.02.2021, online available at https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/vorschlag-des-justizministeriums-so-soll-rasse-aus-der-verfassung-verschwinden-1.5194114, last accessed on 07.05.2021.

[4] Barskanmaz, Cengiz and Nahed Samour (2020): Warum der Begriff „Rasse“ im Grundgesetz bleiben sollte. Der Tagesspiegel, 21.06.2020, online available at https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/ist-das-grundgesetz-rassistisch-warum-der-begriff-rasse-im-grundgesetz-bleiben-sollte/25935310.html, last accessed on 07.05.2021.

[5] Auma, Maureen Maisha (2020): Für eine intersektionale Antidiskriminierungspolitik. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, Vol. 42-44, online available at https://www.bpb.de/apuz/antirassismus-2020/316764/fuer-eine-intersektionale-antidiskriminierungspolitik, last accessed on 04.05.2021.